This article was first published in the National Post on April 16, 2022. It is being republished with permission.

by Tom Bradley

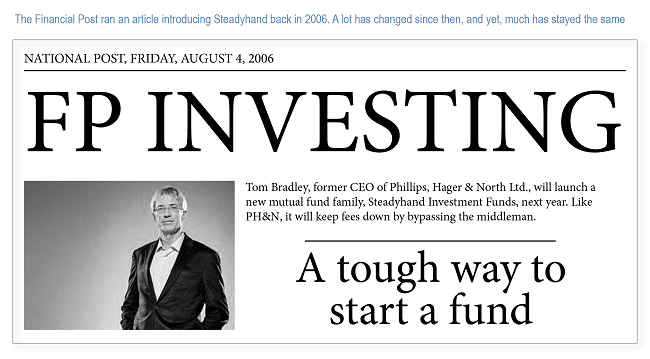

This month marks our firm’s 15th birthday. I’ve been using the milestone to reflect on how much has changed since we started, and how much has stayed the same.

In 2007, I still coveted my CD collection, was forever hopeful the Vancouver Canucks would win the Stanley Cup and was bemused by a new device called the iPhone. Back then, robo-investing wasn’t a thing, and wealth managers (they weren’t called that yet) were just starting to embrace digitization. The Steadyhand blog we developed to communicate with clients was unique, as was delivering client statements online.

Many of the industry innovations that followed were geared to trading. As such, there are now more active stock traders than ever. A number of things came together to make this happen, including universal access to company information, low (or no) trading commissions, easy-to-use apps, the emergence of the own-forever tech giants, and a plethora of new industries (for example, cannabis) and specialty exchange-traded funds to invest in. A long-running bull market didn’t hurt, either.

Another feature of this period was the bifurcation of financial advice, with the wedge being the size of a client’s account. Full-service brokerage became less available to the average investor as advisers were incented to focus on wealthy clients. Everyone else was pushed to bank branches, discount brokers or robo-advisors.

In the meantime, independent, advice-only planners, who were scratching to make a living when we started, are now struggling to keep up with demand.

Changes to the economic and geopolitical landscape could fill five seasons of a Netflix series. I’ll touch on the few that would make the trailer.

Over 15 years, the world order dramatically changed. China began flexing its muscles while the United States seemed intent on losing its competitive advantage. Unemployment turned to labour shortages. Environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) factors gained a foothold in the management of both corporations and portfolios.

The biggest macro trend was unrelenting monetary stimulation. The use of debt was encouraged and, lo and behold, government and household borrowing significantly increased. We’ve reached a new level of complacency around “spend now and pay later.”

Nobody rode the cheap money trend better than private-equity managers, which went from niche to mainstream while using amounts of leverage that public companies would be crucified for.

But, as the saying goes, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Since we cut the ribbon, there have been no Canadian Stanley Cup winners. Investment fads came and went with regularity, each accompanied by a wave of FOMO (fear of missing out). We were implored to buy asset-backed commercial paper, index-linked notes, cannabis, special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), cryptocurrencies, meme stocks, options, oil and gold at various times, Cathie Wood and ETFs using leverage and covered calls.

These investments had one thing in common: they were a windfall for the industry. The buyers, on the other hand, had varying degrees of success.

Meanwhile, investors’ obsession with the U.S. Federal Reserve was unwavering, and overreacting to current events became a regular pastime. As is always the case, however, the news noise and related volatility had little impact on long-term returns. On any chart, market indexes trended up and to the right.

Unfortunately, the problems we tried to address in 2007 are still issues for investors today. Too many portfolios are not linked to a goal. Transparency around fees and returns is abysmal. Sales is rewarded over service. And while fees have come down, they remain frustratingly high in some areas, particularly with respect to advice.

But despite all the changes and challenges investors have faced, the key elements of investing remain the same.

The market is driven by companies innovating and growing profitably, not by what the Fed says. In the short term, stocks are more volatile and unpredictable than the businesses that underlie them. Time in the market is more important than timing the market.

Being diversified is the right thing to do for everyone who isn’t Warren Buffett. Asset mix and fees are important determinants of returns, as is investor behaviour. At market extremes, big mistakes are easy to make and have a lasting impact.

Extra due diligence is required when financial products get more complex. The promise of lower volatility invariably comes with lower returns.

The investment landscape will have changed 15 years from now (as will how I listen to music), but the keys to successful investing will continue to be patience, discipline and the power of compounding.

We're not a bank.

Which means we don't have to communicate like one (phew!). Sign up for our blog and join the thousands of other Canadians who appreciate the straight goods on investing.